The Shells

Hundreds may have walked this route before us, and yet, each tide washed away new traces.

Instinctively, I turned my head from the book towards the sound. My colleague was standing at the door knocking.

A week ago, I had asked him if he could give me feedback on a story draft.

“Come in,” I said, smiling, “have a seat.”

He was holding a notebook as he walked towards the empty office chair. He sat down at the ash-grey desk, removing the rubber-band from his book. With the edge of his hand he began to flatten a double-page of notes.

We talked about the fate of a man our age that day, a captain of the Royal Navy who sank into deep depression on the storm-lashed shores of Patagonia almost two centuries ago.

What sticks with me from that afternoon is the hesitating glance my colleague gave the moment before he rose from his chair, some time into our talk. Moving towards the door, he closed it with a gentle push of the handle.

Hands on his thighs, he took a seat again. After a few breaths, he bowed his head, gazing at his notes on the story of the captain. After a deep inhale, he returned to the conversation.

“That’s exactly how I have been feeling,” he began.

As a vessel holds a liquid, a story can give us hold.

Its walls, familiar and strong, are the horizon and limitation alike in which human beings lend meaning to the contingencies of life.

Some imagine the decisions on a line of work, for a person, or a field of study as the beginning of a straight line. For others, it is the beginning of an episode that leads to new ones, to something whose vector is still unknown.

Sometimes, it is an unexpected encounter, a blow of fate, or a simple phrase which can make a familiar vessel crack or shatter.

Stories provide rooting as human beings transition between the familiar and the unknown, and each transition raises the question of how to frame the new in that shared striving for continuity.

There is a strong connection, I like to think, between the way we feel and the concepts we apply in writing and re-writing the narrative of who we are.

How much room do we leave to revise that story as we move through life? How agile are we in integrating experiences of failed expectations into the stories we like to tell? And how do we, individually and collectively, make sense out of times when old narratives fall apart, and the new ones aren’t yet in sight?

Sometimes, venturing into the fog is our best option.

Some months before that conversation in the office, I had been trying to write my way out of a hole. Lacking perspective, it felt as if my academic efforts had been a sunk cost.

It was around that time that a close friend of mine asked if I would like to join her on a journey to Argentina. In the beginning, I hesitated.

My last travel experiences had left me questioning. At the bottom, there was the fear of feeling like someone who couldn’t find a way to enjoy what attracted many others.

In the end I went on the trip, borrowing a friend’s backpack – I couldn’t remember anymore where mine was.

The voyage led us to the far south of the American continent, to the photogenic sides of Patagonia with Perito Moreno Glacier and the mountain ranges near Torres del Paine and FitzRoy.

What I encountered were hikers queuing at bridges in national parks, people asking me to step out of their pictures, cars and busses lining up at the parking lots. It was at the glacier, less than an hour away from an international airport and accessible through a visitor platform, that I witnessed scenes like the one of a lady wearing a Frozen sweater.

I had wondered about the small ladder on the platform for some time. Then I saw the woman beginning to climb its two steps, one hand holding tight to the top. Towering in front of her, a man in a photographer’s vest patiently observed her ascent from a slightly higher ladder.

While the woman, somewhat shakingly, began to unfold her arms above the protective railing, the splintering from the glacier behind her grew louder. During the ice’s crescendo, dozens of visitors shuffled over the platform’s metal grille flooring around her.

Under thunderous noise and a hundred lenses, a mighty chunk of ice crashed into the lake below the terminus.

When the ice fell, the man in the photographer’s vest pressed his shutter’s release too, eclipsing anything from his vantage point but the one visitor in the Frozen sweater with the glacier behind her.

My initial doubts resurfaced as the scene unfolded before my eyes.

What am I doing here?

I didn’t know if any of the other visitors felt that way as they returned from the railing, smiling about the latest harvest of photographs they inspected on their screens.

Was there anything more substantial, I wondered, that our invasive presence yielded than a barrage of images that perpetuate an illusion?

It was one of the evenings before my friend had to return to Buenos Aires that I started browsing in the hiking guide that would soon travel back with her.

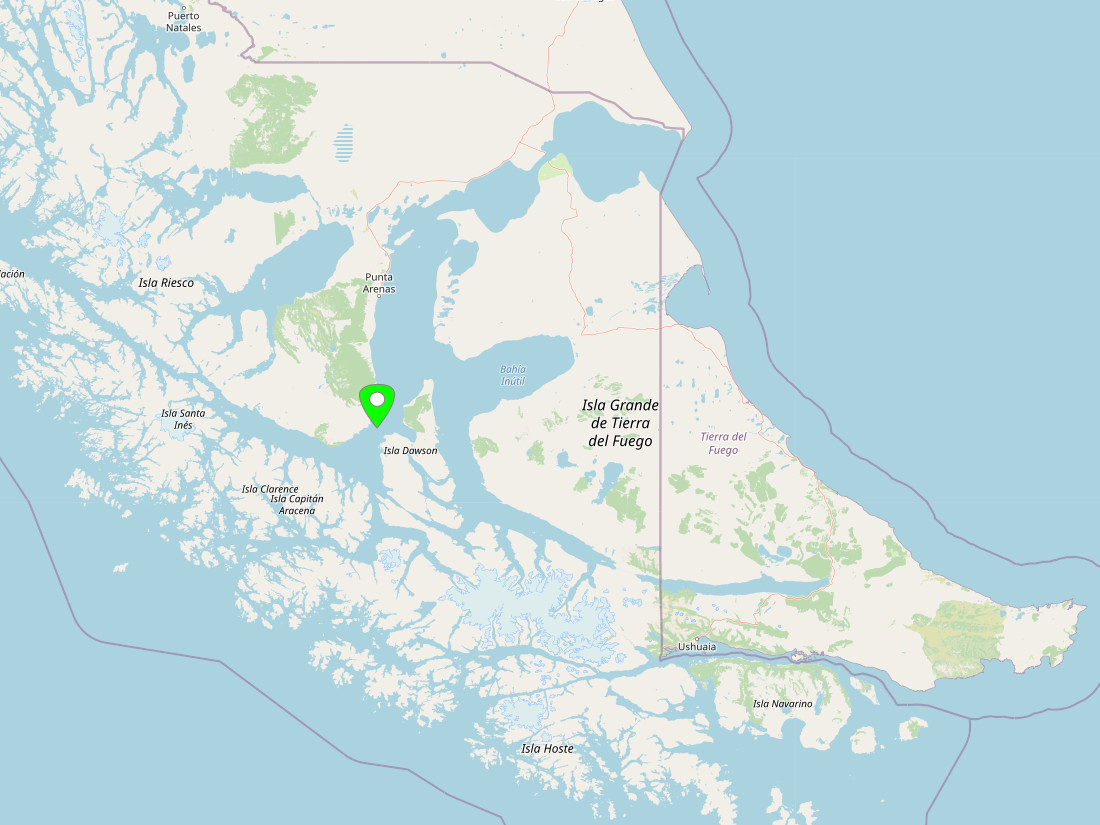

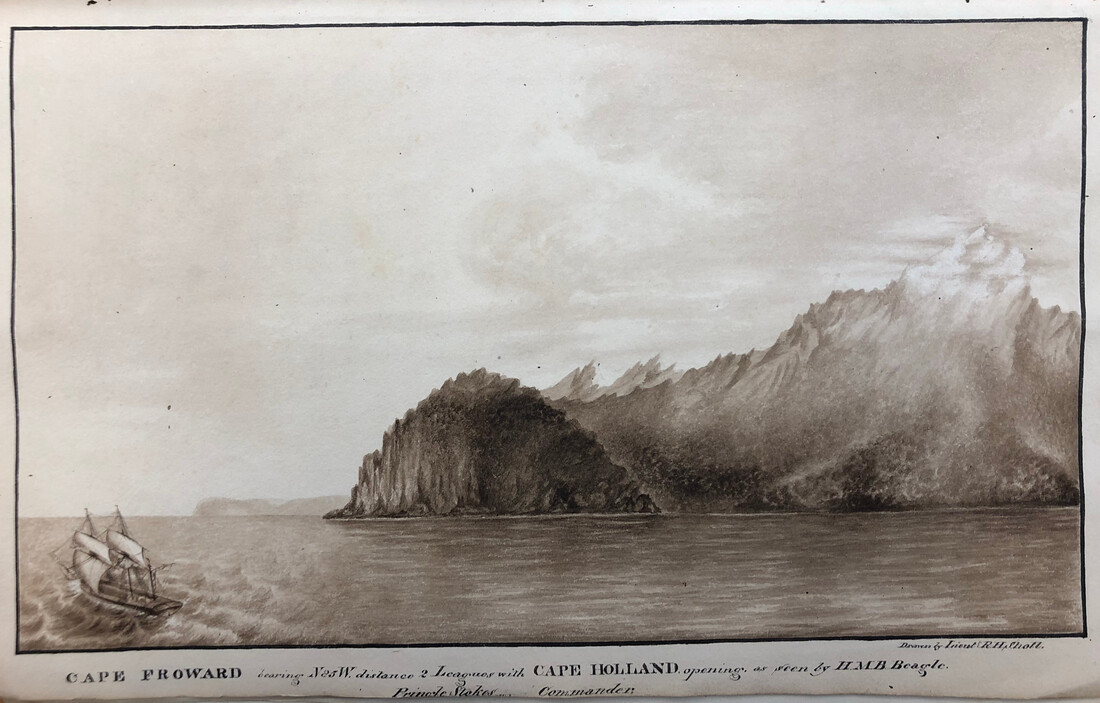

In contrast to the trekking-Meccas of Torres del Paine National Park and the area around the FitzRoy-massif, I read, where thousands of outdoor-enthusiasts flock during the summer months in Patagonia, the trekking-tour to Cape Froward is one of the areas in Patagonia which are only about to be discovered.

A multi-day hike is the only way to reach the southernmost tip of the continent, the guide explained, leading along the beaches of the Strait of Magellan. It was one of the few geographical extremes of the globe that cannot be reached by car.

A week later, I had boarded a bus travelling down the dirt road that hugged the southernmost part of the Strait. Reggaeton rhythms from the driver’s radio mixed with the hum of the engine.

A few days a week, the bus leaves from Punta Arenas, the last harbour in the south of Chile. The town had seen better days. Since the Panama Canal opened its locks in 1914, most vessels have avoided the perilous and time-consuming route around the tip of the continent.

Through tinted windows, I saw the peaks of Tierra del Fuego on the other side of the Strait rise into overcast skies. My companion for the Cape was sitting on a seat in the opposite row, his eyes fixed on the bleak horizon.

Some days before, I had walked into a hostel in Punta Arenas, hoping to find out the latest conditions about the trip.

“Cape Froward? Try the silent guy over there,” the girl at the reception had said.

I first spotted Brett sitting at a hostel table, poring over a map in a shiny black down jacket and woollen beanie covering his head.

Our eyes met briefly. Then, his view returned to the grids. His eyes rose again when I took a seat at his table, asking him about the Cape. The winds had smashed his tent during the first night of a solo-attempt, he told me.

Eventually, we decided to shop for a tent each and try again, together.

An intermittent beach is the only land route to Cape Froward, viable when the low tides on the Strait uncover a narrow strip of gravel, cliffs, and plates of volcanic origin. On our maps we had marked three rivers we needed to cross on the way. Twice a day the rising saltwater blocks their flow, damming the rivers up to impassable heights.

“The two of you make a good team,” the girl at the reception joked when we schlepped out our gear and supplies for five days.

“You’re bald and bold.”

To the sound of the Reggaeton tunes, I held watch from the bus over the right side of the dirt road. Overlooking one of the bays, a dozen white crosses rose from the slope.

“The English cemetery,” I said to Brett, nodding in the direction of the crosses. “They keep the original of one of them back at Punta Arenas.”

In memory of Commander Pringle Stokes RN [Royal Navy], HMS Beagle, who died from the effects of the anxieties and hardships incurred while surveying the western shores of Tierra del Fuego, † 12-8-1828.

There had been something about these lines that drew me in the moment I read them. It was the space between, what they left unsaid. The more they tried to veil the cause of Stokes’s death, so it felt, the greater the desperation grew in my imagination that this man must have incurred leading his men on these desolate shores. What happened to him, I wondered, jotting down the inscription from his brittle cross in the Museo Salesiano.

“Sounds pretty bleak,” Brett said after I had finished reading the lines to him. “A Navy guy, you say?” For a while, our gaze rested on the stretch of the Strait that widened on the opposite side of the cemetery.

It wasn’t much later that the comforting hum of the bus fell silent. With a hissing noise, the doors opened.

A dog was sitting next to the final stop, waiting along the dirt road, patiently. From where we left the bus, some final kilometres remained. The last stretch of the road down the Strait terminates in a dead end. It is the trailhead to Cape Froward.

On the beach nearby, the tide was coming in as we began walking towards that end of the road.

“The dog is following us,” Brett noted after some hundred meters. We need a name for him, both of us agreed after the dog still stuck with us some kilometres further on.

I looked at the German shepherd with his rich coat and kind eyes. One of his ears hung down in two halves, ripped perhaps by barbed wire.

“Let’s call him Splitsy,” I proposed.

Fin de Camino, white letters soon spelled out on a jade-coloured sign. “End of the road”.

“Cape Froward. Geographical landmark where the American continent begins, as marked by the Cross of the Seas,” a further street sign announced right behind.

“Today: Mineral Water – Coffee – Tea,” said a cardboard sign that leaned on the makeshift counter of a nearby trailer. Parked on floppy tires, the last outpost of gastronomy was out of business. From a stick as a flagpole, a Coca-Cola-banner was flying in the sky above with flapping noise.

Slipping through the guard rails, Splitsy led the way down to the beach.

Beyond the last signs loomed the stretch of land that would be our trail for the coming days, lined by impenetrable forests in a darker shade of green. Twice a day, the sea rises to the roots of the trees. Before we left, I had written down the low and high tides of the coming week in my notebook.

With a slurping noise, the wet gravel sucked up our boots. Dark patches remained where they emerged from the ground again.

By the time we finally reached harder ground, I was treading on with a hanging jaw. For some time, I stood breathing, my head bowed over a slab of conglomerate rock.

Somewhere down there, I spotted a blotch of colour shouting through the grey ground. The crab must have been exposed to the sun for some time, the fiery red betrayed. Kneeling down on my gloves, I examined its remains, feeling the warlike spikes that rose from the lifeless shell.

When I picked up my head again, still panting, Brett was treading on ahead of me. Seeing him lean into the blasting headwinds, effortlessly, it didn’t come as much of a surprise to learn that he was a US marine. He had served in Iraq and Afghanistan, he had explained. Stoically, he moved on with his 20+kg backpack.

Bay after bay, we continued on the beach that day along metallic crescents. “An elusive hinge of silver”, the Spanish poet Góngora had called the Strait.

On the horizon behind Brett’s silhouette, the Strait spilled into the coves of Tierra del Fuego, sharing its shade with the low clouds. In the brief moments they lifted, the peaks of Isla Dawson emerged, perhaps 10 kilometres away.

In the 1970s, Pinochet had Nazi fugitives erect concentration camps on the far shore of the barren island, invisible from the Strait. They received those who dared to speak up against the dictator’s regime. Smothered by subantarctic storms, the dissidents’ voices died away in this utmost recess of Chile.

In one of the bays we passed, some rays of rare sunlight flickered on brittle concrete under the surf. Whalers from Europe had hauled their catch up here on concrete ramps, dying the bay in shades of crimson.

I picked up a few hooks and winches that reached out from the sand, corroding away in the salty spray. In a rusty heap, the links of a wound-up chain lay inseparable.

A century of tides must have fused them together, I thought, watching a tawny delta spread in the sand below.

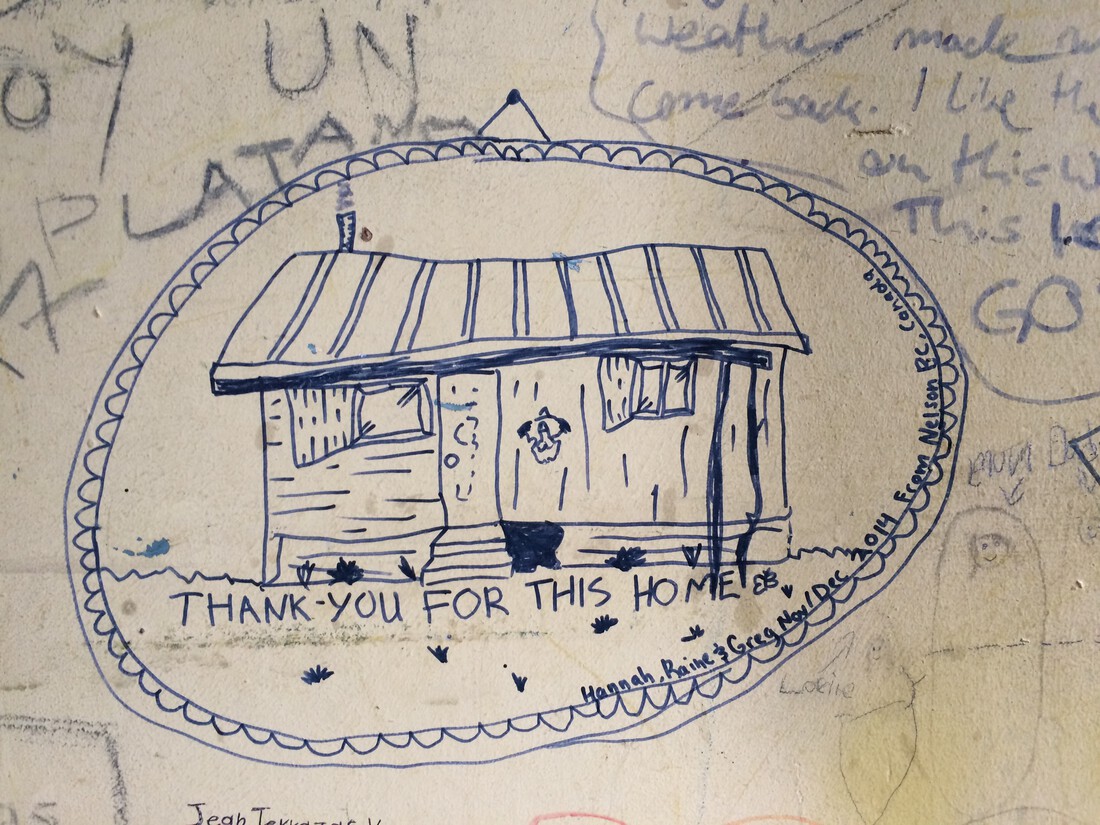

Before the tide came in again, we entered a small forest, looking for a place for the night. On a tongue of land behind the marram grass, we encountered an abandoned cottage, nestled in a small clearing.

In my friend’s guide I had read about the one roof on the way to the Cape. The southernmost settler on the American continent had been living in this hut until 1993, cultivating the surrounding land.

Over time, storms had blown some of the Antarctic beeches over onto the grass. A gentle wind was pulsing through the blades as we approached the house, carrying over the sound of the nearby sea.

In greyed timber siding rose from the ground, each plank fitted tightly against the other. I examined the interstices, thin as pencil lines.

Someone had worked hard to make this place a home.

Above, plates of ribbed tin in tawny brown served as the roof. Many seasons had battered the house. Below, next to the woodshed, one of the hut’s corners was patched in metal, the ribs still betraying the oil barrel that had been repurposed.

The bleached skull of a ram greeted us next to the front entrance. Left and right of the door, two window frames still shone invitingly in a bright yellow. Between the door jambs, a rusty chain was rocking in the wind, thumping on the brittle door.

No lock held the door in place. We easily removed the noisy chain and entered. Through the windows, erratic light streamed into the main room, stirred by the leaves outside. Around the frames, yellow chipboards held some insulation in place.

Scribblings of travellers covered the walls, in three alphabets.

In one corner of the shack stood a rickety bed frame, fashioned from splintery planks. A few wooden shelves remained on the walls, simple boards.

The fragrance of charred wood still lingered in the air, blending in with that of rotting timber. The chimney pipe had broken away from the iron stove that dominated the main room, exhaling a fan of soot over the floor.

It was a smell that brought to mind the hut my grandfather had built for me. I had spent the happiest days of my childhood there under overcast skies, on the farm where my mother grew up, nestled between spruce-covered hills.

In the afternoon, when my grandmother heated up the stove, the smell of the wood stove mixed with the crisp air. Next to their woodshed, my grandfather had nailed together the small cabin from discarded top logs, topping the structure with some sheets of corrugated metal.

The hut had a door that was my height and even a window cut-out. Listening to the patter of the rain on the ribbed roof, I laid out the stones and pinecones, the shards and rusty nails I had gathered roaming in the forests and the farm buildings.

The musty smell still in my nose, I watched the patterns of light and dark moving on the floor of the settler’s hut.

Soot draped down the top of the window panes. The glass had turned lacklustre.

Plastic wrap had replaced some of the panes. In rhythmic shocks, gusts of wind now bulged the make-shift covering, causing the wooden supports to shudder.

On the sill below, conches and carapaces spread out in the dim light. Hikers had brought in the harvests from the nearby beach, decorating the place that provided shelter for a night.

Inspecting the array, I opened the plastic box where I had placed the crimson crab a few hours ago. Placing it on my palm, I examined the spiky shell once more, its legs standing off like dry branches of fir.

In restaurant windows at Punta Arenas, I had seen photographs advertising outgrown specimens of what I thought I was holding on my hand, King Crabs that grow up to an arm’s length. As my view now wandered over the conches and turbinates on the window sill, I spotted the carapace of one of them. Next to the mango-sized shell, I placed its tiny relative.

Taking a few steps back, I marvelled at the array to which I could add.

Above, drops of rain began playing on the tin roof. We pitched camp for the night outside in the lee of the hut, on soft grass instead of the wooden floor. Not far away, the winds had demolished Brett’s tent. For me, it was the first night in a tent in many years. Outside its walls, Splitsy inhaled deeply every other minute.

From the cabin door nearby, I could still hear the iron chain knocking – in vain. A quarter century earlier, a few candles may still have flickered in the draft on the window sill, casting a silhouette of the man who listened to the winds outside.

Who was this settler, I wondered, and what drove him out here?

None of the things this man had gathered remained on the shelves. Only the hut itself, the hollow echo of a former existence.

Once more, the chain’s thumping.

Was there a sense of relief when he closed that door to never return?

Reaching for my backpack, I took out the box with my notebook. The pages that opened in the light of the head torch mainly contained dates and places. Then, the times of the tides on the Strait. In scrawly handwriting, the inscription from the museum at Punta Arenas.

Turning the pages, I felt the smooth white paper cling to my fingers. A smell of the sea still was rising from my hands. It had stuck to my fingers since I had placed the crab on the window sill.

The bags of shells we brought back from family trips to Greece, I thought on the next inhale.

Re-read that one poem by Ekelöf, I jotted down before I wrapped the rubber band around the book again and turned off the lamp.

it is late on earth now and already fate is closing my eyes but in my dreams I am a child again searching for shells with light and torch in the twilight that settles on the lonely beaches of my childhood roomGUNNAR EKELÖF, Kosmisk sömngångare

A rainy mist veiled the beach the next morning. Anything beyond the outer points of each bay lay in fog. Deep clouds cut the peaks across the Strait to stumps.

The low tide had scattered white conches over the beach like specks on elephant skin. Following Splitsy’s lead, we returned to the rhythm of bay following bay.

It felt as if I was moving lighter on the ribbed ground, hardened by the retreating waves. Hundreds may have walked this route before us, I thought as I followed imprints Brett’s boots left in the sand. And yet, each tide washed away new traces.

Around his boots, Brett’s beige trousers were flapping around his ankles in the headwind. On the backpack above, I watched his water-bottle dangle from a carabiner, covered in stickers with flags of New Zealand, Nepal, and South Africa.

Reaching for my notebook, I returned to the damp pages that recorded the tides. FR ↓ 00:58 ↑ 7:18 ↓ 13:31 ↑ 7:46, the row of pencil letters shimmered. We shouldn’t lose time, I realised, returning the book as I continued walking.

The rising tide had already begun to dam the widest of the rivers when we reached its bank. We dropped our bags, took off our trousers, and tied our boots around our necks. With bare feet on the icy ground, we stood shivering, facing the gusts and the spray from the Strait in speedos.

When the winds abated a little, a salty breath rose from the leeside, carrying the smell of conches and crabs. Fragments of mussels scattered the banks like shards of an infernal vessel.

It was a Stygian world, and Charon had long taken leave.

With each step that I followed Brett towards the water, the coarse sand became squishier, gnawing higher up our ankles with its abrasive teeth. Soon, the icy ground was sucking the feeling out of my legs.

Grinding my teeth, I focussed on the bottle that was dancing from the backpack in front of me. Its tapestry of stickers hinted at colours that had long faded away from this surrounding.

Where’s Splitsy, I startled the moment before the dog paddled back into my field of vision, seemingly effortless in his fur coat.

We had passed the deepest part of the river when the soles of my feet went numb. Leaning into my poles, I dragged them towards the far bank. A burning sensation flared where my leg emerged from the waterline again, the wind chilling the wet skin.

On the far side, I pushed myself up the bank, dropping my gear on the ground. We had crossed the river.

In haste, I began rubbing the exposed parts of my body dry. Near the bank, Brett still sourced some boggish water from the river while I was getting dressed. While the earthy liquid heated up on the stove, the feeling slowly returned to my legs, the icy numbness yielding to a painful prickling.

On Brett’s foot, sticky water was still refusing his sock. I noticed the intricate tattoos running up from his instep. The patterns and motifs had blossomed with each travel, he explained.

For a while, I followed him through the Himalayas in Nepal and the Drakensberg in South Africa, episode by episode.

Next to my boots, Brett’s water bottle was lying in the sand with its patterns. I noticed a large sticker.

Oregon gives me wood.

Back home, Brett told me, his father had often taken him out camping in the mountains. He spoke warmly about his dad and the skills he had taught him.

The tone changed when he came to his later story – it did not include a college fund. After high school, he joined the Navy. It was his chance to see the world. And it was a story of close friends who had enlisted along with him, many of whom did not return.

Soon, steam rose in plumes from the gas stove. Having poured the coffee, Brett blew into his mug, holding its steel tightly to gather some warmth.

After military service, he continued, he went back and forth in jobs in the security sector, transitions which were not always smooth. Sometimes, a job, his parents, and a love left behind meant splitting himself across three continents.

His eyes lit up again as he came to speak of his travels again that filled gaps as he changed assignments.

“Had you known all this before, would you still have chosen the same path?” I asked Brett.

After some time, he had found his answer.

“Many of us spend our thirties adjusting decisions we made in our twenties.”

Across the Strait, the peaks still lay veiled in a hazy curtain. Drops of rain were starting to hiss on the stove that was cooling in the sand.

Since we left the cottage, we hadn’t noticed anything suggesting a human presence. It was a landscape in which man disappeared.

Brett’s gaze wandered up the coast again. “What drives a man down here?” he asked as he tightened the hood on his jacket.

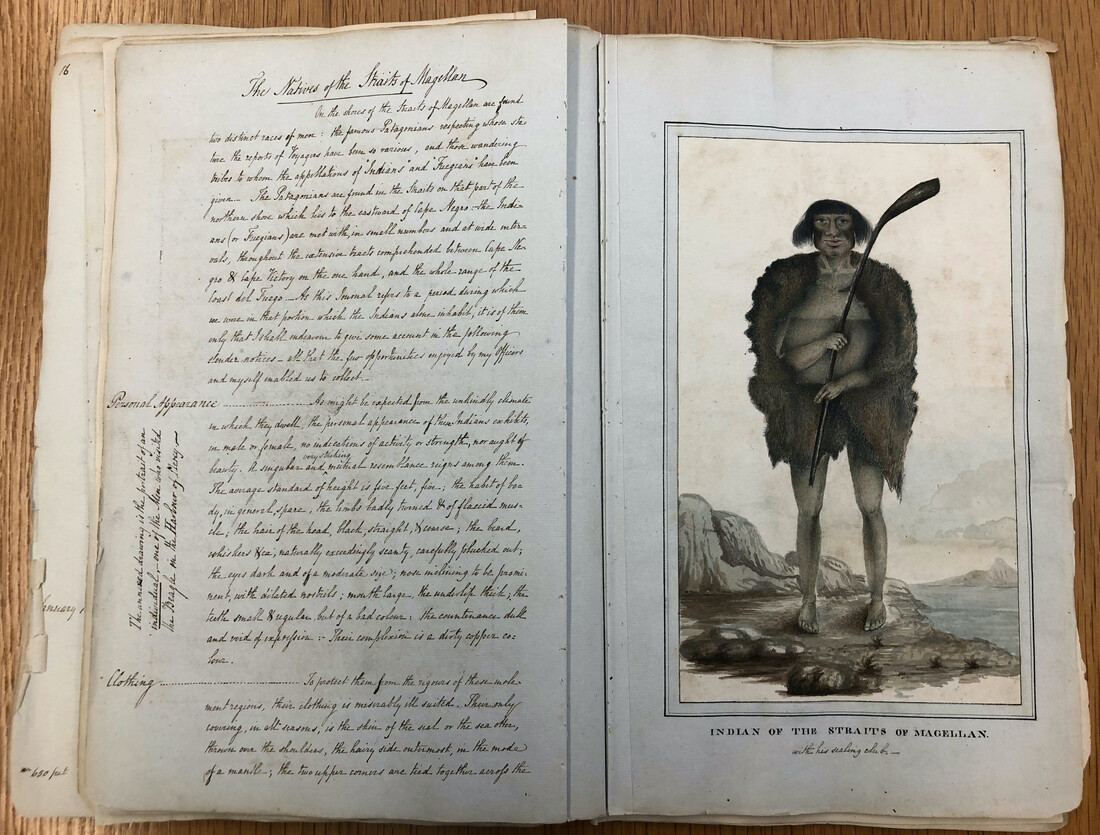

“I’ve read that there once were natives living on these shores,” I said after a while.

“From their boats, they dived for crabs and shells in the icy inlets. On the beaches they lit fires to warm up again. Their fires were what gave Tierra del Fuego its name.”

“The early drawings by European sailors show them with naked legs, wearing nothing but a piece of fur,” I added.

“When was that?” Brett asked.

“Late 1820s,” I said. “First voyage of the HMS Beagle. Darwin’s later ship.”

For a while, we watched the storms chase clouds over the horizon, taking sips from our cups. The idea of facing these winds in nothing but a guanako fur left us shuddering.

On the river in front of us, the gusts now were churning minuscule crests upon the surface. Time to end the coffee break.

The last spots of blue had disappeared from the sky when we continued along the beach, conversing about the people who once called these shores home.

The Yámana were one of the people who lived under these bleak skies. In their language, the human soul was as rich in shades as the clouds passing over their heads. And the creatures on their shores, too, resonated with inner experiences they all shared.

šöfkili s[ubject]. The crab after casting its shell before the new one is perfectly formed. a[djective]. Heartless, timid, spiritless, tame, dull, unenterprising, low spirited, dejected. THOMAS BRIDGES, Yamana-English: A Dictionary of the Speech of Tierra del Fuego

The crab and human beings share that liminal state after leaving behind an outer shell, a corset that stopped fitting the person inside.

It was a hopeful image for that phase of vulnerability, insecurity, and listlessness, a sensation that the Yámana integrated as part of a growth cycle that connected human beings with the animate world around them.

In the 19th-century Navy, the word ‘depression’ was still reserved for mercury falling in the barometer.

In 1827, when her first captain sailed the Beagle along the shores we wandered, his task was to produce maps of the Strait that linked the British Empire with markets in the Pacific. Much of what the young officer saw of this world was through the lens of his instruments.

The journal that Captain Pringle Stokes drew up on his first surveying mission includes an account of the people the Beagle encountered on the coasts. Shocked by their scanty clothing, he described them as unspeakably poor.

The richness the Yámana had found on the bleak shores remained invisible to European crews of the time. If there was any reason to study the language of the ‘primitives’, as Darwin wrote on his later mission, it was to facilitate the missionaries’ work.

“Remember the captain’s cross we passed at the Navy cemetery?” I said to Brett. “I think Pringle Stokes lacked a language to make meaning of what he experienced up north.”

“So what happened to him?” Brett asked.

“His supervising officer sent him up the Strait again, on a second mission. Stokes’s task was to survey further up the western coast, in late autumn. The most brutal conditions on an uncharted sea left him in constant fear for the safety of the crew. For days, they didn’t make progress while the winter storms thwarted their attempts to survey.”

“Captain Stokes felt like he failed to fill his uniform. For days, he didn’t return from his cabin. The maps he signed were produced by his most capable officer. The thought of disappointing his supervising officer kept him in a leaden grip. In the end, he waited until the last ration had been dispensed before they made the final turn around Cape Froward, back to the rendezvous point.”

“The ships met in that bay we passed in the bus. At some point, his supervising commander became suspicious and began interviewing the Beagle’s crew. That was when Stokes shot himself.”

For some time, Brett fell silent, his gaze resting on the end of our bay. Somewhere beyond lay that utmost tip of land, “as marked by the Cross of the Seas.”

Asking a tentative question, he returned to the conversation.

“Have you ever thought about writing these stories down?” ◆

All translations and photographs are my own unless noted otherwise.

Acknowledgments

For their support I would like to thank Peter Davidson, Alex Franklin, Libby Rohovit, Sophia Schwemmer, Brett Watson, and a person who knows I am grateful.

For their support of my research on Pringle Stokes, I have to thank John Williams and the wonderful staff at the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office

^ An elusive hinge of silver: Luis de Góngora, Soledad primera, 456–7 (“de fugitiva plata / la bisagra”).

^ it is late on earth now: From Gunnar Ekelöf, Kosmisk sömngångare (1932): “nu är det sent på jorden, och ödet sluter redan mina ögon men drömmerna förvandlar mig återigen till ett barn som letar snäckor med ljus och lykta i skymningen som faller över strändernas ödsliga barnkammare”.

Ekelöf was one of the most acclaimed poets of Sweden in the twentieth century. His compositions, inspired by the Surrealists, do not follow modern rules of interpunctuation and spelling. I imitated these aspects in my translation.

See the poem in the historic edition of sent på jorden (Stockholm 1932) on literaturbanken.se.

^ šöfkili s[ubject]. The crab after casting its shell: Tomas Bridges, Yamana-English: A Dictionary of the Speech of Tierra del Fuego, ed. by Ferdinand Hestermann and Martin Gusinde, Mödling 1933 (repr. Ushuaia 1987), p. 153.

As late as the 1860s, the British missionary began studying the language of the Yámana. He died before its completion. More than thirty years later, his son published Bridge’s life work in in 1933.

The 32,000 entries of Bridge’s dictionary remain as fragments of a world now extinct (browse the dictionary on archive.org).