The Lifelines

"Will the UN

Fly, or fall from the sky?

Asked the northern bird."

国連は

飛ぶか、落ちるか

と、北鳥。

Will the UN

Fly, or fall from the sky?

Asked the northern bird. Haiku by SIR TIM HITCHENS

A summer in Sweden, 1961 – Childhood memories.

“September was still very summerlike that year, and we swam in the sea every day and enjoyed it to the full. When we left for home from the seashore, Marlene’s mother stopped at a kiosk to buy us ice cream.

Marlene and I stayed in the car, waiting and waiting. We watched her mother standing in front of the kiosk, with an ice cream cone in each of her hands.

In the end she came back to the car with two melting cones. She told us that the plane that carried Dag on a mission in Africa had crashed.”

“Hammerskjöld. Dag Hammerskjöld.”

“Dag Hämer.. – Hämerslück – how do you say that?”

“Dag Hamerskjöld – it’s a name I probably couldn’t pronounce. Hamerskjöld?”

“I speak a bit of Swedish …”

“Dag Hammars – Oh my god – k –jöld?”

A cloudy day in Hamburg, Germany. A large billboard overlooks a labyrinth of metal fences funneling streams of commuters over a square. Office workers in casual clothing, speaking with absent business partners through ear pods. Travellers pulling their trolleys in haste. In a corridor winding between construction machines, they rush over the strip that remains of the wide square linking Dammtor station with the nearby subway.

Many months ago, the city put up the billboard, unfolding a vision of what the Dag-Hammarskjöld-Platz may look like after reconstruction. Few of the passersby stop to take notice.

“Does he have something to do with the gardens?”

“Alright – he was a Norwegian globetrotter, wasn’t he?”

“He was a former UNESCO or NATO president, something like that.”

“That’s the first UN – the first? – in any case an important UN Secretary-General.”

When his phone rang at night on April first, 1953, Dag Hammarskjöld dismissed the news of his appointment to the UN as an April Fool’s joke. A week later, the Swede officially became the second Secretary-General of the young organisation.

Western powers and the Soviet Union had finally been able to agree on a candidate from whom they didn’t expect any trouble. They hoped to have found just that in the diplomat known, if at all, as an intellectual. To most leaders Hammarskjöld simply was a blank.

A few weeks later, the Swede with the unpronouncable name disembarked from the plane in New York to take office.

‘Call me hammer-shield,’ he used to tell journalists. ‘That’s actually what it means.’

To the great surprise of many who had appointed him, Hammarskjöld had no intention of keeping a low profile at the UN. With diplomatic talent and a clear vision of his mission, he negotiated in international post-war conflicts such as the Suez Crisis. It was under Hammarskjöld’s leadership that the UN first dispatched armed Emergency Forces that became known as the Blue Helmets.

Soon, democracies emerging from colonial rule hopefully turned to the UN as protector of their self-determination. One of these countries was the Republic of the Congo.

None of the conflicts in which Hammarskjöld negotiated during his two terms as Secretary-General of the UN proved to be a greater challenge than the Congo Crisis, the aftermath of which is still felt today. After half a century of colonial rule, Belgian forces retreated from the Congo in 1960. A short time later, secessionists and mercenaries, backed by mining companies and foreign intelligence agencies, vied for power in the young democracy under President Lumumba.

In early 1961, Lumumba was assassinated. The UN Blue Helmets deployed to the region found themselves in the middle of a humanitarian crisis. Time and again, Hammarskjöld returned to the Congo. At the brink of exhaustion, he sought solutions and dialogue with leaders.

On September 17th 1961, the Secretary-General boarded a UN plane at the airport in Leopoldville, today called Kinshasa. The aircraft travelled on an undisclosed route through the night towards the Katanga province to negotiate a cease-fire with rebel leader Moise Tshombé.

It was in the afternoon of the following day that search planes spotted its smoldering remains which had cut a swathe through the forest. On the approach to Ndola in today’s Zambia, Hammarskjöld’s plane had dropped out of the sky.

To this day, the cause of the crash remains unclear.

When Hammarskjöld’s friends later cleared out his apartment on the Upper East Side, they found a manuscript on the bedside table. It contained a personal diary that Hammarskjöld kept throughout his adult life. It is a testimony to the doubts that raged behind the diplomat’s austere facade, the inner struggles of the tasks that never stopped challenging the idealist that Hammarskjöld was.

The pages contained various writings – contemplations, maxims, poems; some of them with a specific date, or at least with a year. For the year 1959, there is a collection of more than a hundred poems written in the Japanese haiku tradition.

With the manuscript, Hammarskjöld’s friends also found an undated letter. In it, he shared his thoughts about his diary with a Swedish colleague: ‘It was begun without a thought of anybody else reading it,’ he writes. ‘But, what with my later history and all that has been said and written about me, the situation has changed. These entries provide the only true “profile” that can be drawn. That is why, during recent years, I have reckoned with the possibility of publication, though I have continued to write for myself, not for the public.’

Poeticised by W.H. Auden, Hammarskjöld’s private writings appeared in English in 1964. Published under the title Markings, the book now counts among the classics of spiritual literature.

A deep passion for poetry links the biographies of Dag Hammarskjöld and Sir Tim Hitchens. As a diplomat, postings in the service of the British Foreign Office took Hitchens all around the globe; to Paris and Africa, to Pakistan and Brussels, to Afghanistan and eventually Japan.

Like Dag Hammarskjöld, Tim Hitchens has been reading and writing poetry for most of his life. And ever since he began learning Japanese in his early twenties, the haiku has been among his favourite forms of expression.

“The power of Dag Hammarskjöld’s poetry also comes from the inherent privacy of it,” Tim Hitchens says, “the fact that though he formally gave permission for it to be published after his death, it wasn’t intended to be read during his lifetime. There is something voyeuristic in a sense of entering into this private discussion with himself and with God, that is not really intended for us, but we’re given the privilege of allowed to be in there.

It links a little bit with his style as a diplomat, which was very … there is a famous phrase of his, you know, ‘I never discuss discussions’. He would do his discussions on some highly topical or sensitive issue and wouldn’t say anything about it in public, because he was entirely private.”

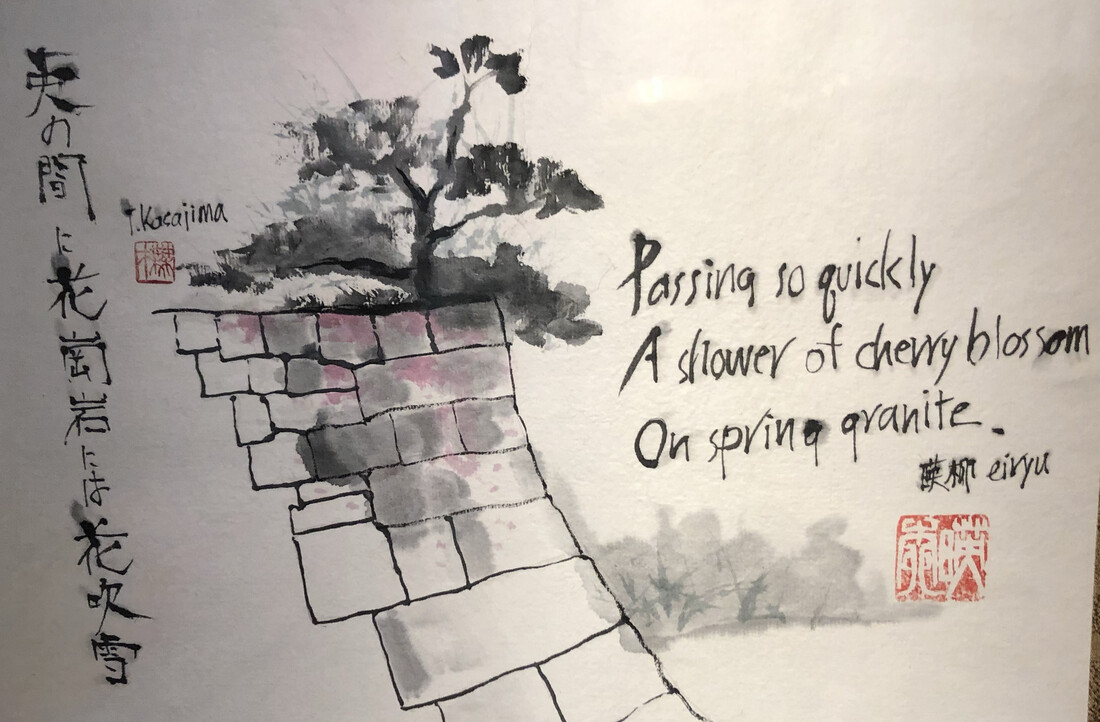

Tim’s four-year ambassadorship in Japan began in 2012 and coincided with the rise of Twitter. Posting as @UKAmbTim the haiku he wrote and tweeted in Japanese eventually reached more than 7000 followers. In 2019, he published a book of the posted haikus with their English translations and water-colour illustrations. Here is a sample:

All the while worrying I

Try my hand

At haiku

SIR TIM HITCHENS, Twaiku (p. 55)

“We were encouraged to do some of our work on Twitter,” Tim explains, “and communicate and engage with the public wherever we were on Twitter, and it seemed to me a very good thing, therefore, to use Twitter in Japanese to engage with a Japanese audience.

In Japanese, like any of those East Asian languages which use characters, a single character contains a wealth of meaning. And each character is both a subject, like the word ‘tree’, but it can also convey lots of different meanings and hints from the design of the character. So 140 of these Asian characters is a much richer diet than 140 letters in English.

I realised if I used poetry, which itself is a very compressed form of expression, I could fit an awful lot in a piece of Japanese verse. And of course haiku was the obvious way to do that because it has a format that one could work within. So I started doing my poetry in haiku form in Japanese.”

“There is a tradition in Japan of poetry,” Tim continues, “which is not simply writing a poem and putting it out there, but you write a poem and send it to somebody, and that person can then write a poem back to you that echoes or builds upon your poem. Or they can send it to somebody else who writes the poem that has a link and then a circle of poetry is formed, so communication through poetry was an established art form.

I discovered that when I would write a poem, there was a Japanese gentleman who would, with beautiful illustrations, draw pictures inspired by my poetry. And I discovered curiously enough that he was fact a friend I’d lost touch with 30 years before, so we’d both been travelling the world together. I used to write these poems and he would then quite often write a response in a picture form.”

“At a certain point, people said, ‘that’s really quite fun, you ought to publish it’. That’s the origin of the book which I published. We called it Twaiku, it’s a little joke on haiku and Twitter, so it was called a book of twaiku.”

“The haiku that I wrote tried to follow more the basic assumptions of haiku,” Tim explains, “so it was not 17 syllables, it was 5 syllables, then 7, then 5. It almost always tried to have a season word, so a word that indicated what time of the year it was, and it always tried to have a twist of some kind in it, where you suddenly think ‘Ooh, that’s not what I was thinking’.

And those are the three elements that I tried to constrain myself with, whereas Dag Hammarskjöld’s poems are constrained into 17 syllables, but not necessarily 5-7-5. They don’t have a word relating to the season, particularly, and they don’t always have a twist, in fact, they don’t often have a twist. The constraint of 17 is what he chose, and that produces a wonderful kind of poetry.”

Sjutton stavelser

öppnade dörren

för minnet och dess mening.

(Seventeen syllables

Opened the door

To memory, to meaning). DAG HAMMARSKJÖLD, Markings, 1959 (p. 175)

Dag Hammarskjöld’s haiku on the seventeen syllables opens a cycle of more than a hundred he composed in 1959. The three-line poems revisit places from his youth, or from travels he undertook as a young man and diplomat.

Hemmet sände mig

till öde rymder.

Få söker mig. Få hör mig.

(My home drove me

Into the wilderness.

Few look for me. Few hear me.) DAG HAMMARSKJÖLD, Markings, 1959 (p. 180)

Some return to vaguer places of his childhood, to deep feelings of loneliness he continued to experience throughout his life. Born as the youngest son to the former prime minister of Sweden and raised in a Protestant surrounding with strong moral beliefs, Dag Hammarskjöld grew to be an idealist. Many poems in his Markings negotiate the doubts he faced on this path.

Sleepless questions

In the small hours:

Have I done right?

Why did I act Just as I did?

Over and over again

The same steps,

The same words;

Never the answer. DAG HAMMARSKJÖLD, Markings, 1961 (p. 209)

“He was in a very lonely place because of challenges, of what he was trying to do in the world he was operating in,” Tim Hitchens says. “So I think his poems have a great emotional depth to them, and that comes also from his childhood as well. Clearly he had an exceptional childhood, both highly privileged, but also a childhood where his emotion was meant to be kept constrained. I think that comes out in the poetry as well, which is deeply private.”

Many leaders who met Hammarskjöld the diplomat describe the sense of integrity he radiated. Those who met him in private could feel the sense of moral duty that defined him.

Karin Wastel remembers meeting Dag Hammarskjöld when she was a child. At the age of six, Karin went to live with Dag’s older brother Sten, his wife Ulla-Stina, and their daughter Marlene in the early 1950s.

Karin’s single mother had accepted a new job that involved a lot of travelling. Through a newspaper ad, she looked for a family to take care of her daughter. One of the families that responded was the Hammarskjölds.

“Dag wasn’t yet Secretary-General when I moved in. Almost everybody knew that a Hammarskjöld had been prime minister. I don’t know if they talked about it.”

What was he like, the prime minister’s youngest son, who, every once in a while, would pay a visit to his older brother and his family?

“He was just Sten’s brother who came for a visit, he blended in with the family. But he was extremely nice and thoughtful, and it means a lot to you as a child when someone cares. He did that a hundred percent.”

Karin remembers one episode from that time in particular:

“One time when Dag came visiting I was lying in bed with a fever. Dag had a book with him for me. It was about a small Gotland-pony.

I just remember how happy I was when he popped up at my bed with the book.”

“He had a strong sense of justice,” Karin recalls, “and he was very, very generous. I was so little, it was difficult to put people into a box. You don’t do that as a child, it’s rather a question of feeling. It’s hard to describe feelings, isn’t it?”

“In the 1950s, diplomats had two very starkly different views of the world,” Tim Hitchens elaborates. “One was the Manichaean, Cold War, spy, really bad commercial behaviour by big mining or tobacco companies, and then you had a high idealism post-War, of what the world could be like.

One of the things if you look at Dag Hammarskjöld he clearly had, is the ability to operate in a pretty brutal world, where he was up against the Americans and the Russians, and South African mercenaries all the time, but he had to be pragmatic to get through.

But he had this deep inner idealism, and the poetry connects with the idealism in a way that makes up a fount of strength for him to go into the negotiations again and again and keep trying to make things better.”

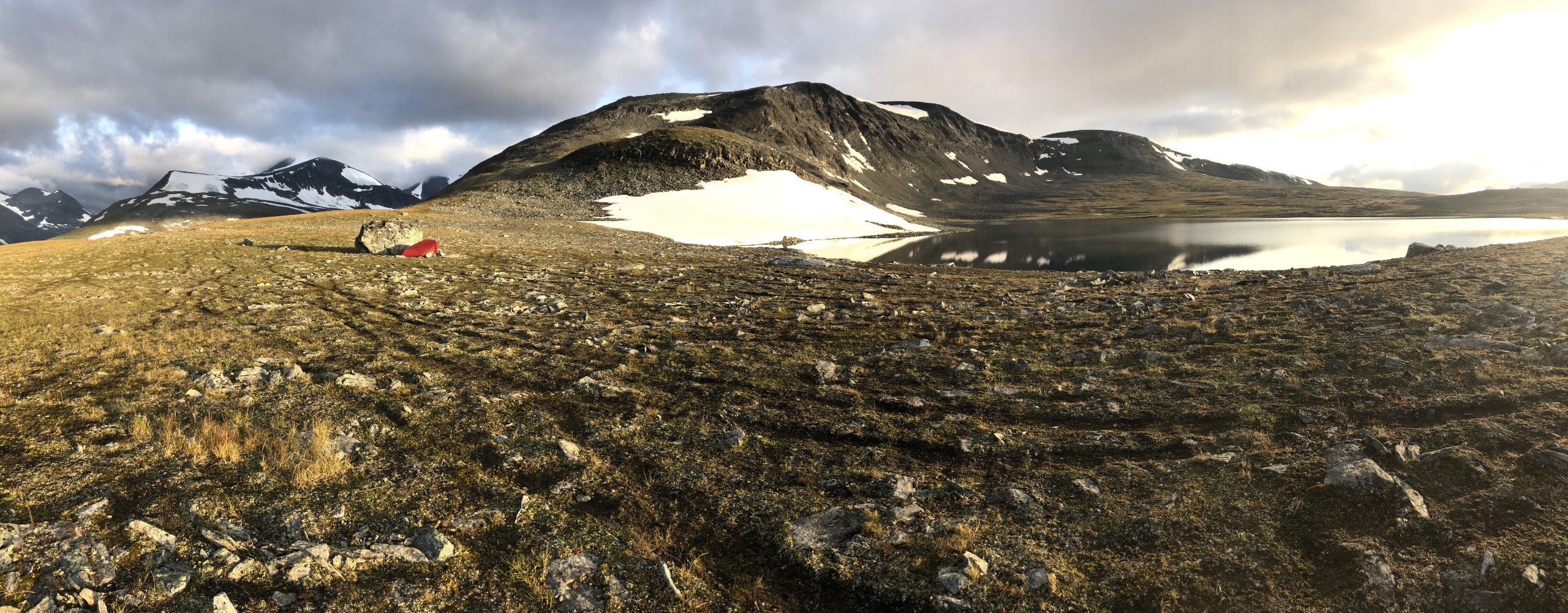

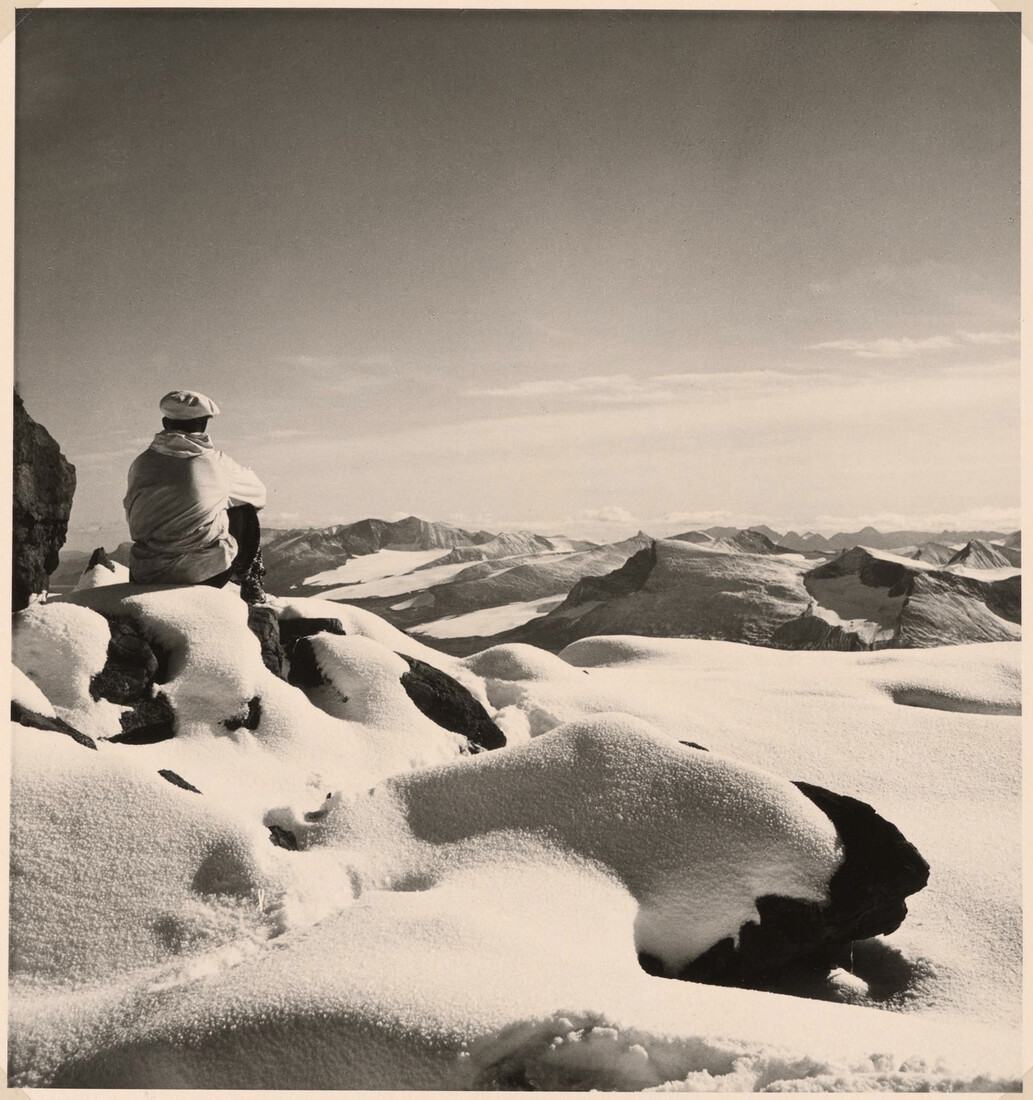

Hammarskjöld had made a habit of tapping into his fonts of strength long before his time at the UN. Colleagues from his days at the ministries in Stockholm remember how he would board a night train to Lapland on a Friday evening, equipped with little more than a sleeping bag, a camping stove, and a backpack filled with bags of raisins and oatmeal. On a Monday morning, Dag would return to office refreshed from the hiking tours in the north.

Vit isranunkel,

ensam, bland stenarna.

Frost där skuggan faller.

(White glacier crowfoot,

Alone among the stones.

Frost where the shadow falls.) DAG HAMMARSKJÖLD, Markings, 1959 (p. 184)

In the harsh climate of Sweden’s north, the first blossoms of the glacier crowfoot herald the coming spring. Retreating to remote places above the Arctic Circle was Hammarskjöld’s way of reconnecting with something larger, something that embraces all life on earth.

Up north, in isolated places like Sarek National Park, he felt part of something that connects humans and non-humans alike, something that brought him deep peace and rooted him.

Poetry was Hammarskjöld’s way of giving a voice to this deep, sensitive understanding of the world around him. It was a side he kept mostly private throughout his life. As he writes in one of the haiku found after his death:

Ensam i sin dolda växt

fann han gemenskap

med allt växande.

(Alone in his secret growth,

He found a kinship

With all growing things.) DAG HAMMARSKJÖLD, Markings, 1959 (p. 191)

Since the time of the old Japanese masters, experiencing nature with all senses has been a key element to haiku. For his book The Narrow Road to the Deep North, a poet like Bashō would seek out the one willow where a fellow poet had rested ages ago, basking in the same shade until the farmers had planted the last straw of rice.

Playing with the literary tradition and capturing the sensual impressions that the coming and going of seasons stir are key elements in Tim’s poems such as this one.

From the hard earth

Emerge new buds.

An infant voice. SIR TIM HITCHENS, Twaiku (p. 26)

“I think it’s no surprise that the haiku comes into its own in the ‘50s and ‘60s,” Tim Hitchens explains, “just with people like J.D. Salinger and Jack Kerouac and all of those people, the counter-culture people, who are pushing back at an American industrial culture which is really very heavy and big and confident and political, and into something that is fragile and reflective and transient, and something that is being lost as the American dream advances.

And I suspect that if you spoke to Bashō himself, and some of the great haiku poets in their era, they would probably have spoken with exactly the same kind of vehemence about — they wouldn’t have said industrialisation, but they would have talked about commercialisation, and the city growing, and the encroachment of man upon nature, and capturing man’s relationship with nature before it disappears. They’d probably have described it in exactly the same strength then, as we do now.

So this poetry isn’t simply nostalgia for an age that was, this is a consistent human obsession, capturing beauty before it’s too late and it’s overrun by humankind.”

Hammarskjöld-Platz lies between Dammtor station and Planten un Blomen, the large park in Hamburg’s city center. Since 1990, it has been home to Europe’s largest Japanese garden. Plants and trees from Japan surround a pond, with a tea house at its center. On a quiet morning, wind caresses the leaves of willow trees.

Hammarskjöld’s encounter with Japanese tradition was one primarily mediated through literature. Among the books his friends found on his night table was an introduction to haiku. He never visited Japan, neither privately nor as a diplomat.

“My poetry comes from quite a happy place,” Tim Hitchens admits, “a place where I felt very much at home in Japan and at home in the work I was doing, and at home in an environment with a family that is very warm and supportive. So I don’t have any of the deep existential angst expressed through my poetry, that he has. And indeed, it’s quite true that my poetry or my haiku was definitely about sharing as it was written and trying to get a dialogue.”

Tim’s proficiency in Japanese has been key to using poetry to this purpose. As a poet, he even adopted a Japanese pen-name. Tim publishes as Eiryu [暎柳], a name consisting of two characters.

“Most great Japanese poets choose their names,” Tim explains. “Bashō was not Bashō, he chose the name Bashō, and the names evolve over time as well. So when I knew I was going to publish, I thought I would, again slightly playfully, find a name that mattered or made a great deal of sense.

So again I worked with my Japanese friends to look for a name that was appropriate. And if people don’t know how Japanese and Chinese characters work, you will very often have two parts to a character. And on the left hand side you have a sign or picture that gives a sense of the kind of word you’re talking about, so it will often be something like ‘tree’, talking about a kind of part. And on the right hand side you have a second picture that gives you a sense of the sound is going to be. So there are a number of pictures which are associated with particular sounds.

And so what you’ve got in ‘Eiryu’, ‘ei’ [暎] has on the right hand side the bit that give the sound ‘ei’, and that is the character always used to mean England [英]. It comes from the early days of Japan encountering England, and it was England ‘igirisu’, ‘ei’ became the sound for the UK or England. But then on the left you have a little sun picture [日], and that is the symbol for Japan. This particular character is therefore one I like a lot, because the sound is ‘ei’, but it’s got this picture, the sun being the writing sign of Japan, the land of the Rising Sun [日本]. On the right you’ve got England.

And then the second is the character ‘ryu’ [柳], which means — ‘yanagi’ is another reading of it, and it means willow. As an English person, willow is associated with England a lot, you know. In this crazy game of cricket that the English love, the bats are always made of willow. And also, the idea of a poet, for various reasons, is often linked to willow. There’s a lovely phrase which is ‘wind in the willows’, which has a great English story to it because it’s a famous book, but in Japan it means picking up a hint in the air, a wind in the willow as it comes through, getting an understanding of what’s going on from a vague sound, so it felt quite appropriate to me.”

“In Japanese religious practices in the Shinto religion,” Tim continues, “the concept of God, the word for God isn’t simply some extraterrestrial form who’s somewhere up in a different area, it’s things that are around us all the time. And that can be things like the sun and the moon, but it’s just as much a wood, a tree, a particular rock, they all have a form of divinity.

So in that sense the landscape around you is part of divinity, in whatever way one wants it to be. It’s still alive and well in Japan in a way that I suspect in Europe is pre-Renaissance, the idea of landscape as divinity. With the Enlightenment we got rid of the divinity in our landscape. I think those are differences between the two countries.”

“As you travel around Japan,” Tim points out, “you have to travel through a lot of big cities to find anything you’d describe as landscape and divine. The Japanese now have developed this ability both to hunt for the farther edges of Japan where the landscape still exists, and also to see the natural beauty in the midst of a really harsh urban landscape, in a way that many of us luckily living in Europe don’t have to, because even our big cities have lots of greenery about them.

In Japan you have to hunt quite hard. Once you’ve found it, its prized amazingly, and that can be either a little bit of moss in somebody’s back garden or a small tree, or some flower. Those things are prized precisely because of the over-industrialised landscape that is the general truth.”

“When I first went to Japan in my mid twenties, just married,” he remembers, “I lived in this place Kamakura which was on the South coast. My wife and I were sitting one evening on the beach, looking out over the sea, and we could see in the distance Mount Fuji. We said to each other, isn’t this just idyllic and a wonderful spot to be?

But then we remembered that we had a three-lane highway just behind us. And we’d completely forgotten that if we turned our backs and looked, it was a horrible industrial sight. But we’d selectively chosen to concentrate upon the bit of what we could see which was the water and Mount Fuji.

I think one does that a lot, in Japan. One blanks out quite a lot of the landscape that is ugly, and concentrates on the absolute beauty that one sees in a certain space in front of you. That certainly became part of what I naturally did.”

As a young man, Dag Hammarskjöld had sought and found such unspoilt beauty in the distant corners of his country, above the Arctic Circle or the remote coasts of southern Sweden. Many of the poems he later composed echo the sense of deep belonging and inner stillness that the memories of such places could instill.

Denna morgon

fyllde fågelsången sinnet

med nattens svala ro.

(This morning

The singing of the birds filled his mind

With the night's cool peace.) DAG HAMMARSKJÖLD, Markings, 1959 (p. 194)

In writing haiku, Hammarskjöld rekindled memories that lay far back in time, far across the Atlantic. It was a way to give voice to a rich inner world, to hold fast to insights that provided sustenance on his path.

However, time off-duty was rare during his terms at the UN. Around 1960, there were only a few weekends at a summer cottage in Upstate New York, or brief walks behind the fences of Central Park.

As the Congo Crisis escalated, Hammarskjöld rarely had the chance to tap into his fonts of strength. Those around him could sense how his mood became darker and darker as he faced the human tragedy unfolding in Africa.

“People often talk about what the Japanese aesthetic is,” Tim Hitchens points out, “and somebody once described it to me this way, that the Japanese aesthetic is, you’re standing on a precipice, you trip, you fall down the precipice, you can see down below that you’re going to die in the river, but you just grab hold of a stone briefly, halfway down, and there’s a little flower on it, and it’s the pleasure of seeing that flower before your grip slips and you fall to your death.”

‘Do you still have faith in man?,’ one of his closest friends asked Hammarskjöld in mid-1961, ‘meaning the individual on his own, not in mobs or masses or political parties. Until then Dag had always answered positively, but this time he looked sad and pensive as he said, ‘No, I never thought it possible, but lately I have come to understand that there are really evil persons — evil right through—only evil’.

On 17 September 1961, Dag Hammarskjöld and his party left from the villa of a diplomat friend in Kinshasa. Later that day, he would board the plane that would take him to the negotiations with rebel leaders.

Friends later noted that the bed in his room had not been slept in. Dag had spent his last night outside, in the garden, waiting for the birds to greet the morning with song.

So how do you say his name?

“På svenska uttalar man namnet ‘Dag Hammarskjöld’!” ◆

For interviews and for their support we thank Tim Hitchens, Karin Wastel, Karin Erlandsson, Steven Tester, Thomas Davies, and Libby Rohovit.

Script and production: Bernhard Schirg and Bastienne Karg.

Post-production: Bastienne Karg.

Speaker: Amanda Lee.

The following sound files have been used in the audio file:

https://freesound.org/people/TOC1/sounds/194373/ CC 0 1.0

https://freesound.org/people/YleArkisto/sounds/254511/ CC BY 3.0

https://freesound.org/people/klankbeeld/sounds/179209/ CC BY 3.0

https://freesound.org/people/YleArkisto/sounds/253280/ CC BY 3.0

https://freesound.org/people/Erdie/sounds/35051/ CC BY 3.0

https://freesound.org/people/daverose/sounds/130754/ CC BY 3.0

https://freesound.org/people/malg0isx/sounds/559868/ CC BY-NC 3.0

The cover image of this article shows a drawing from a letter by Bo Beskow to Dag Hammarskjöld, 15 August 1958. National Library of Sweden, MS L 179:1:10. Published with the kind permission of Maria Beskow.

We quote Hammarskjöld's Vägmärken in the translation by Leif Sjöberg that was 'poeticised' by W.H. Auden (Markings, London 1964). The Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation has put a further edition and translation by Bernhard Erling online.

Contrary to the date mentioned in the feature (2019), Tim’s book of twaiku appeared in 2016. See Tim Hitchens, Twaiku eiryu: taishi no kushū, with illustrations by Takashi Kasajima (Tokyo: Shuppan Kyōdōsha, 2016).

The Swedish originals are taken from Dag Hammarskjöld, Vägmärken, Stockholm 2006. They were spoken by Karin Wastel.